TL; DR: Effective nudges through digital prevention are hard to nail, and so much is about influencing and ‘boosting’ the wider environment. I reflect on my experience in the GP waiting room, brag about my local grassroot activism, and sum up some of our work quantifying the benefits and value of digital prevention.

Over the last two weeks I’ve been thinking a lot about the healthcare system and how digital is only one element of a wider service provision that results in sustained behavioural changes. A lot of it was triggered by my experiences outside of work but helpfully, work has also allowed me to engage with this topic.

Recently, Ralph Hawkins shared on Slack a great article by Hertwig et al. (2025) on the value of moving from individual behavioural nudges to boosting “the competences, opportunities, and motivations of individuals to act together”. This analysis really resonated with me and I’ve used the framing of nudging versus boosting to structure my thinking.

Reflections on getting nudged

Last week I had to wait for a GP appointment for over 40 minutes and this turned out to be quite illuminating. For the whole time I was waiting, the ‘waiting room loop’ of public health and wider social care announcements on the TV in the reception didn’t repeat a screen once!

There was everything from prevention services (like vaccinations,including paid ads for travel vaccines and the benefit of exercise; to specialised services for people with diabetes) to sexual health clinics and free contraception for under 25s; to what’s an Integrated Care System. I was also pleased to see a lot of information from the Smartphone Free Childhood campaign, which covered awful stats on the negative effects of smartphone use on mental health for adolescents.

For a selection of my ‘favourite’ screens I saw, scroll to the bottom of this post.

I didn’t get to see how long the total loop of unique content would have been but it was fascinating to experience a crude ‘make every contact count’ (MECC)’ nudge intervention in action.

According to the formal definition of Public Health England and NHSE from 2016:

MECC supports the opportunistic delivery of consistent and concise healthy lifestyle information and enables individuals to engage in conversations about their health at scale across organisations and populations

I couldn’t help but reflect on how effective this particular MECC moment was.

- On the surface of it, this should be a faily captive audience because people have already enaged with the health system to be at here and they have to keep an eye on the screen to see when it’s their turn. However, from what I observed this time and on other occasions, the majority of people, at least in my GP practice, are not very engaged and get seen within 5-10 minutes. So my waiting time was a bit of an anomaly. I tried looking at data of the average wait time in practice before an appointment but couldn’t find any (although I found very detailed up-to-date data about most things concerning GP appointments). I also observed that apart from me, no one was taking a very active interest in the screen and only looked up when they heard the little ding that announces the room number for a new patient.

- There’s no personalisation. As mentioned, the topics are fairly diverse and if you only have a short window of time, and multiple of these messages are not relevant to you (because you’re not a parent to a child who may have or about to have a smartphone, or someone with diabetes), you’re more likely to not pay attention altogether.

- It’s not very accessible and especially for people with lower health literacy or engagement, would find it overwhelming. Whilst a few of the clips had obviously been prepared by teams who understand how to do marketing materials and fairly accessible digital engagement, the majority were not. They were poorly (or not at all!) subtitled, the font was often small, many of the explanations were complex. Screens were moving quickly and there was no audio. So I don’t think this is an effective way to target people with health inequalities, who would arguably benefit the most from these types of interventions.

- On the positive side, this type of intervention costs almost nothing to run – it’s certainly cheaper than the flyers available for some of the same topics. To my knowledge, there’s no data to assess the effectiveness but I’ve certainly noticed that the amount of content my GP practice adds to the ‘waiting room loop’ increases every time I’ve been over the last 2 years. So by very spurious and shoddy correlation, I can extrapolate that these messages may work (better than nothing). Even if only 1 in 100 people engaged fully in one of these public health information messages, there could be a benefit to the system.

Earlier this year, I worked with a team that was undertaking some MECC experiments that added content about healthy diet as part of winter COVID and flu vaccination campaigns. The engagement rate was close to 0.1% and we decided to pause the alpha work once the campaigns completed until we have more solid hypotheses and structure to what we want to test. I think that was the right choice, especially given the rates of engagement weren’t particularly high.

I can see how effective MECC can have an important and interesting role in engagement. However, making it effective – namely, personalised, timely and relevant – is not easy due to massive technical and legal complexities. Simply using techniques and mantras from digital marketing and retail to ‘upsell’ is not effective MECC!

My little bid to boost the system

The other experience that influenced my perception of how we ‘boost’ the environment to promote public health was my recent ‘crusade’ against the cotton candy machine in the local leisure centre and gym. Yes, you read that right.

Our community centre decided to install a huge, flashy cotton candy machine with a screen that blasts bright cartoons about it, right in the middle of the cafe where all kids pass for their swimming classes. As if to underscore the irony and complete the Wes Anderson tableau-style aesthetic, the cotton candy machine was right next to the ‘health checks’ machine that measures weight and blood pressure. I’ve added a picture below because it’s too good not to.

The first time I saw it there was a queue of kids negotiating with their parents to get some cotton candy. My own 3 year old daughter begged me to get her some too but pretty quickly understood I won’t budge.

I was shocked by this setup. So of course, like the neighbourhood campaigns keyboard warrior I never knew I was, I straight away emailed the leisure centre management as well as HQ of the wider company that owns the centre. I also filed a complaint with my council, investigated how to directly contact my local councilors and drafted an email to my MP in case the first steps failed.

After multiple exchanges with the manager, who told me this is a ‘pilot’ but couldn’t tell me the criteria upon which it would be assessed, I was so excited to see this weekend that after weeks of this monstrosity, they’ve finally removed the awful machine!

This anecdote isn’t to highlight how effective my grassroot complaining can be, although I’m pretty smug about it. (Full disclosure: I don’t know who else complained or if indeed the manager cared enough about my complaints and threats to talk to our local MP).

It’s to highlight that “shaping the environment to maximise individuals’ ability to use those competence” is essential to succeed in public health interventions (Hertwig et al., 2025).

And to be clear, to me this isn’t the fault of the leisure centre manager for introducing this attractive, yet extremely unhealthy choice. The economic incentives are clearly not stacked up to work well to promote public health effectively. Initiatives like the ‘sugar tax’ have resulted in tangible improvements to kids’ health, as validated by public health research. But much more is needed.

Digital can make tangible contributions to the uptake and efficiency of administering prevention services and interventions. No matter how amazingly designed, inclusive, and personalised the digital services we launch to help with prevention are, they won’t be enough on their own. When the environment—physical, economic, or social—is not conducive for people to make healthy choices, particularly kids and young people in their formative years or vulnerable individuals experiencing health inequalities, we will always be lagging and spending money on treatment, not prevention.

I’m hopeful that moving policy and implementation (including digital) closer will help to bridge that gap and address system-level levers as well as service and channel interventions.

The value of digital prevention

Finally, at work we’ve been doing some thinking on the benefits and value of personalised prevention services, to inform our strategic business case.

It’s been an interesting process, trying to assess how digital personalised prevention of risks and conditions would impact things like improved health outcomes as well as the NHS and wider economic productivity. Conor Lyster came up with a really excellent framework based on the main risks that result in preventable conditions, to try to measure how our work can be measured to support the wider benefits we will (in theory!) generate.

Ultimately, so much of our work is still unproven, which is why we’re now focused on piloting end-to-end ‘thin slices’ of use cases to validate our risky assumptions in practice, à la ‘the strategy is delivery’. A lot of digital prevention resides more in the ‘nudge’ camp. However, I’m confident we can deliver meaningful change and achieve these sustained behavioural changes.

Why? Because we have really great teams working on these problems and approaching it the ‘right’ way – with users at the heart and designing for the edges, with empathy and respect, with passion and conviction.

A selection of my ‘favourite’ screens I saw at my GP practice

A cartoon video about heart disease – ‘HEART DISEASE – The End’

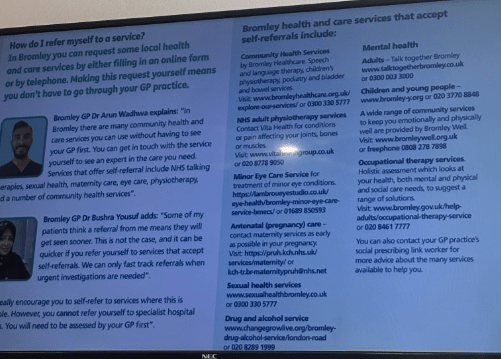

Explainer about how to self-refer to services. Very useful but only was on screen for 10-15 seconds so difficult to actually follow (unless, like me you take a picture or decide to google it).

A cartoon video with no subtitles! I can’t tell what it was about. If you have any suggestions, let me know 😀

Leave a comment